File photo.

Raccoons tipping over the trash, skunks trapped under the house, rats running rampant through the sewers—urban wildlife has existed since the first mouse found its way into a fable. But it took a while for the term to make its own way into households, and when it did, the coyote led the pack.

Coyotes have been living in cities for decades—according to the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS), they’ve been interacting with humans for over 100 years. So have raccoons, skunks and rats, but lately, fear and anger have been directed at coyotes in particular because of a feeling of threat that they pose to humans and their pets. This fear, whether out of experience with an attack, a lack of education about urban coyotes, or a willingness to act on it, has become increasingly articulated during the past 10 or so years.

At the Long Beach City Council meeting on August 11, councilmembers will vote on a recommendation to the city manager to conduct a study of Long Beach Animal Care Service’s (ACS) Coyote Management Plan (which can be accessed here, along with the text of the council recommendation) and the possibility of establishing a mitigation plan to address public concerns over a growing presence of coyotes in Long Beach and accompanying attacks on pets.

“We plan to review the current structure and determine its effectiveness, and if we find it ineffective, propose additional measures that could keep our communities safe,” said Fifth District Councilmember Stacy Mungo. Mungo is bringing forth the recommendation along with councilmembers Daryl Supernaw (4th District) and Roberto Uranga (7th District).

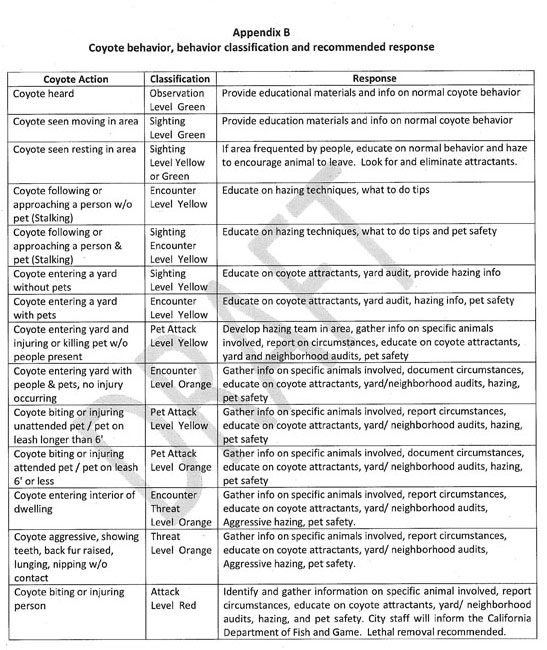

The management plan as it stands comprises three parts: educating the public about coexistence with coyotes, enforcement of laws and regulations that prohibit feeding wildlife, and ensuring public safety via a tiered-response system. The system consists of four levels: green in response to a sighting; yellow if a coyote is lounging or continually moving through an area generally inhabited by humans; orange if one acts aggressively toward people or attacks a domestic pet; and red if there has been an investigated or unprovoked attack on a human being. In the latter two cases, city staff and the Department of Fish and Wildlife (DFW) will intervene to locate and eliminate the coyote, likely through euthanasia. Sick, injured and aggressive wildlife are the only cases in which an animal may be removed or subject to euthanasia.

Summary of coyote encounters and actions taken, courtesy of ACS

Coyotes are attracted to food sources, particularly during breeding season when they have to feed their pups.

Generally, there’s been plenty of food for them to eat in urban areas—the desert couldn’t compete with such a groaning board: unattended garbage cans and bags, fruit from trees (yes, coyotes will eat anything, and anything includes fallen fruit, especially when it’s fermenting. Sort of like a preprandial aperitif—a Wiley Wallbanger), rodents and food left out for pets. And the pets themselves.

What’s more challenging is they’re very smart. But why coyote/human/pet encounters have so recently become prevalent is a matter for speculation. They’ve been attributed to drought, climate change, and overbuilding on undeveloped land, which destroys habitats of both coyote and prey. Lyndsey White Dasher, director of humane wildlife conflict resolution for HSUS, has an additional theory. Coyotes, she said, have no predator other than human beings in urban environments, and humans have unwittingly made it easy for them.

“Coyotes have no competition,” she said at an educational seminar in Seal Beach last December—click the link to watch. “They’re very smart. If we’re making it easy with food and garbage, and the coyotes come in and nothing bad happens to them, they tell their friends.” Thus, coyotes gradually lose their fear of humans, and our pets can become supper for them.

As with many issues revolving around animals, opinions about how to handle the issue are polarized. Some community members feel that this is a human-caused problem and that coexistence with coyotes is essential, and others want to get out the torches and pitchforks.

Last October, Seal Beach at the urging of some of its residents began a trapping-and-euthanasia campaign against coyotes, which involved the use of a mobile gas chamber. This reportedly turned out to be not only a cruel way to kill the animals—one online news medium quoted an apparently horrified and contrite council member as saying that the gas caused the coyotes to choke and spasm—but also ineffective.

Coyotes, Dasher said, are very good at controlling their own population; females will breed more prolifically in order to replace missing members. Seal Beach has since abandoned its program in favor of education.

Mungo affirmed that the coyote mitigation plan that she and the other councilmembers propose doesn’t include trapping and gassing. She also cited the numbers of coyote incidents after Seal Beach’s short-lived killing project, saying that it appeared as if there hadn’t been any trapping at all.

“And hunting (within city limits) is illegal,” she reminded anyone who might, despite statistics, think of taking it into his or her own hands.

Mungo described several community- and city-based actions that she and her fellow councilmembers are considering to help mitigate coyote encounters, as follows:

- Removing food sources—covering trash cans, taking in pet food, gathering up ripe fruit from trees, and implementing a quicker pickup of dead animals by ACS. Animal corpses also provide food for coyotes.

- Clearing out reported coyote dens. A couple have been observed around town, and Mungo hopes to make this action a community project.

- Organizing volunteer hazing groups, which could also be done through ACS.

Meanwhile, it’s important for all residents to take precautions against coyote attacks; besides the food, they include use of hazing techniques, clearing landscape where coyotes can hide, and having a leash short enough to pick up your dog when walking it in case of attack. Retractable leashes don’t lend themselves to this.

And please keep your pets, particularly cats, inside. Educated feral-cat feeders always pick up food after the feeding time is done and also provide an escape area for the cats. But a wandering cat is easy prey, and not just at night.

“Cats are coyote food, which they can smell from a mile away,” said cat rescuer Annelle Baum. “It’s a myth that coyotes hunt from dusk till dawn. This was very clear to me when I saw a coyote running down my street in Seal Beach at 10:00AM on a hot Sunday morning.”

Dasher said only one percent of coyotes enter residential areas and attacks pets. Of course, if you speak to anyone who has lost a pet to a coyote, it’s easy to see why they’d band together with others and insist on having the animals’ heads.

Likely anyone seeing a pet or a child under attack would take extreme action—protective instincts generally trump any logic. And there have indeed been incidents of coyotes attacking and in two cases killing children—again, a comparatively minute number. The deaths were across the North American continent, but it’s terrible to imagine happening.

But to get down to basics, even if some people won’t be convinced by the necessity to coexist, it remains that killing the animals doesn’t solve the problem and may exacerbate it. Therefore, everyone has to pull in the welcome mat and quit providing them easy eats, whether by accident or design—some people mistakenly feel it necessary to feed wildlife because they’ll starve otherwise

It remains to be seen how effective the new mitigation plan will be, not because the actions aren’t well conceived, because they are. But the education has to reach an awful lot of people, and even when it does, acting on it is a next step that not everyone takes. In summation, which is more difficult: changing coyote behavior, or changing human behavior?

Read Stephanie Rivera’s LB Post article for more tips on coyote management. ACS has a comprehensive wildlife program that can be accessed here.

“Animals are not brethren, they are not underlings. They are other nations, caught with ourselves in the net of life and time.”

~ Henry Beston, American author and naturalist