On Saturday, September 8th, the University Art Museum is hosting an opening reception for three new exhibitions, all featuring painting.

In From The Vault, Executive Director Christopher Scoates delves into the permanent collection to showcase works of Abstract Expressionism. Linda Day: Swimming in Paint will showcase the abstract paintings, collage works, and drawings of the popular and celebrated CSULB faculty member who died last year. Rounding out the exhibitions is Patrick Wilson: Pull.

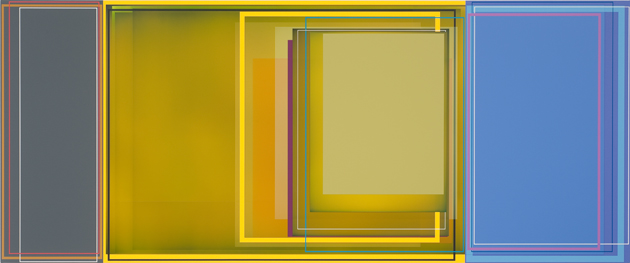

Wilson is a Los Angeles based painter who has developed a highly evolved language of geometric abstraction. Since his graduation from Claremont Graduate University in 1995, his work has been highly sought after by prestigious institutions, galleries and collectors.

“It’s a great place to be,” said Wilson. “I’m thrilled with the way things are currently working out, not only the fact that a number of people are getting to enjoy the work in different venues, in museums and very good galleries, but also that I’m getting to basically live and work in exactly the way I’d always hoped, which is in the studio, full time. I couldn’t ask for much more than that. It’s what I love to do, and it’s been that way now for quite a number of years.

“One of the great things about being in the studio full time is that it gives me a huge amount of time to consider and reconsider the work, to really get to know not just who I am but what it is, what I am trying to do, and want to do. Because of all those hours constantly consuming work visually and mentally, it’s been able to progress fairly steadily. I don’t ever say ‘this body of work is now over. Its time to start the next one.’ My work gradually changes over time and, in the last 15 years, there have been pretty significant shifts.

“Coming out of graduate school, the work was abstract, it was non-objective, but not the way it is now. It was often relating more directly to something in my environment, typically the native landscape, or parts of the built, urban landscape. There was always a reference to my surroundings, an awareness of how and where I lived. Gradually, in that earlier part of my career, things began to be more representational, to the point where I started to notice that rectangles looked like a certain building that I knew. At some point, I gave into that and began using actual imagery in my paintings, developing very open ended narratives.

“It’s very pleasurable to draw certain things, but ultimately it became a restriction since the people were trying, too much, to read a kind of meaning into the work, and that wasn’t really going anywhere that was exciting for me. As I said to Kristina Newhouse, the curator of the show at the University Art Museum, I’m much more interested in ‘art that is’ than ‘art that is about.’ I’d rather eat the meal than the menu. I don’t want to tell people what to think, or what I think. I would much rather set up the situation where they can experience these paintings and come away with their own unique take. It’s sort of like a meal. I don’t want to over analyze the meal. I want to consume it, and take great pleasure in it. I want the work to be generous.

“There is this painting in the show called Bacchus—the god of wine and pleasure—and clearly, that [association] is very important in the work, that it has this sort of sensual quality, that it be pleasurable and not repulsive. I don’t mean that in a superficial way, I think that pleasure, and the pursuit of pleasure, is very important because we usually become preoccupied with things that we need to do, or something that just happened. Life tends to fly by when we are thinking in fast forward, or in reverse. I think that the more often we can pursue pleasure, in whatever form that takes for people, that the more you are in the moment, living in your life.

“There is this painting in the show called Bacchus—the god of wine and pleasure—and clearly, that [association] is very important in the work, that it has this sort of sensual quality, that it be pleasurable and not repulsive. I don’t mean that in a superficial way, I think that pleasure, and the pursuit of pleasure, is very important because we usually become preoccupied with things that we need to do, or something that just happened. Life tends to fly by when we are thinking in fast forward, or in reverse. I think that the more often we can pursue pleasure, in whatever form that takes for people, that the more you are in the moment, living in your life.

“My process is very intuitive. I have said, in past interviews, that these paintings are made ‘one line, one shape, one color at a time.’ It really is a matter of responding and reacting. It has some flow and, in some ways, they are more built than painted because of the sort of rigor that is involved in making them. But even with that amount of time, I’m always looking and always thinking about what just happened, and it really is a gut response. The next day I come in the studio I decide ‘Ok, what has to happen now?’ ‘Is it any good?’ ‘Do I need to cover part of it up?’ and there is a lot of covering up problematic parts of the paint. I hope that what keeps them fresh is the fact that they are more organic in their making.”

About a decade ago, Wilson developed a severe allergy to a component in oil paint that forced him to switch to acrylics. He was forced to reinvent his process, and discover the benefits of this new medium.

“My goal, when I switched over, was to not completely abandon everything. I had to find a way to use the new material with some of my old processes. I have always used dry wall blades to pull paint around, and I wanted to continue that process because I am able to create these translucencies, this sensation of depth, that gives an odd illusion of space that also has a really strong physicality at the same time. The paint builds up and builds up and builds up until there is a physicality to it which is, in some way, at odds with the illusion of depth. I find those two ideas, happening simultaneously, very interesting.

“When I made this shift I discovered that I could pull this paint and achieve a similar effect. I can stack and layer a lot more elements on top of it. The oil paint was very limited in terms of how many times I can tape and re-tape, and the drying time with acrylic has opened up so many possibilities that I decided that this was a good time to reconsider non-objective painting totally. So I lost the imagery entirely and focused on really what my strengths are, which are color and composition, and the idea that they turn into something more. A good painting is more than the sum of its parts.”

The technique has proved challenging. Too much pressure, and the paint is applied inconsistently. Too little, and air bubbles mar the surface, and damage the color saturation. Still, these are challenges that he keeps hidden in the work itself.

“This layering is complex from a handling point of view, but I never really want it to feel that way. I don’t want it to feel difficult as much as I want it to feel nuanced. I never want to trumpet the labor and the work. I would much rather it come across as sort of ethereal, or maybe mysterious, structurally.”

“It takes about six to eight weeks to complete a painting, so I have to work on four or five paintings at once. The other reason that’s important is because ideas can open up in one painting that’s in progress and lead me to rethink how I am working on another painting. That is part of my process that keeps these works evolving. Also, another interesting thing that happens fairly often when I’m working on multiple paintings at the same time is that they tend to become like brothers and sisters or cousins. There are little connections between things, whether its color or proportions, that make them more interesting in a grouping when they are exhibited.

“You can see hints of where I live. There’s no doubt about the sensation of light and haze and smog that is so unique to Los Angeles. Many painters and many artists have talked about this in the past. It’s all in there. The paintings feel like Southern California. To me, I don’t think these could be made in San Francisco, or in New York. I don’t think they would look the same.

“These things are really meant to be lived with. They can function in an institutional setting, for sure, in a museum show or in a corporate collection, but really they are meant to be lived with. It comes down to the type of experience a person has with art, and that is so different when they live with it than when they go out to see a show somewhere. Things are revealed slowly over time. Things you just can’t see in 20 seconds, or 20 minutes.

“I think we have begun to lose our ability, culturally, to slow down and look at something like painting. I think people are maybe more comfortable, at this point, looking at moving images because of our exposure all the time, everyday, to technology. The pace this work is viewed at is really important. I can‘t do anything other than suggest that we slow down a little bit, occasionally. ”

I had the opportunity to speak with Kristina Newhouse, the Curator of Exhibitions at the University Art Museum. She has followed Wilson’s work with interest for many years, and was pleased to present his work in her first curatorial effort at the museum.

“I was absolutely convinced,” she says, “that he would provide me with an excellent show. Moreover, because there is a fad for abstraction right now, I wanted to add to the discourse by showing folks what it looks like when it is thoughtfully and rigorously done. A person looking at Wilson’s paintings in person can discern quality. These works are perfectly executed. They deliver on an aesthetic, formal, and perceptual level in a way that is quite satisfying for viewers.

“As an artist, Patrick has been troubled by the didactic nature of art made in the past couple of decades. It is even reflected in how we talk about reception—we ‘read’ a work of art. In my case, as a curator and a writer, that is practically literal. When I look at an artwork, more often than not, I can tell who the artist was inspired by, what theorists he/she is reading, where he or she went to school, whether he/she is East Coast or West Coast. The average viewer does not have access to this data–hence, it is often like trying to extract meaning from a foreign language. But no-one needs specialized language or education to have a perceptual or intuitive experience.

“Because of the developments in art post 1960, a lot of viewers feel uneasy looking at contemporary art because they do not feel qualified. But they do feel qualified to talk about artwork that operates on an intuitive or perceptual level (hence the ongoing love affair the public has with Light+Space). Patrick gives viewers permission to access a way of thinking and talking about artwork that had been off limits for a very long time.

“I think people will enjoy the exhibition. Patrick is always talking about the need to slow down and experience pleasure. I hope, when people come, they do not rush these works, but take them in at an indulgent, leisured pace. I think that will make their visit more satisfying.”

Patrick will also be at UAM on Tuesday, September 11th, for a free noontime gallery talk. Parking permits are required.

—

The author would like to sincerely thank Amanda Fruta, the UAM staff and student interns for their kind assistance in transcribing his conversation with Patrick.