We all come to accept that Santa Claus is not real, that the jolly white-bearded men we encounter this time of year in suits red with white trim do not live at the North Pole. We come to accept that on Christmas Eve there is no reindeer-pulled sleigh coming to a rooftop near you.

But a secret that none but a few of the world’s children ever learn is that Santa Claus is a spirit—not merely a spirit in the sense of an idea, but a soul that moves across the face of the world, for brief stretches of time benevolently possessing this or that person playing Santa Claus for children. For fifteen minutes Santa enters the body of Chief Johnson at the Golden State Fire Department’s holiday party for underprivileged youth. Ten minutes later he is looking out through Mr. O’Connor’s eyes at the Anytown Shopping Mall in Middle America. Suddenly he inhabits Dr. Smyth as he makes his costumed Christmas rounds in the pediatric cancer ward at Northeast Hospital. It’s a process that confounds the small number of physicists and spiritualists who know of the phenomenon. All they can say for sure is that Santa moves from body to body in a manner not completely unlike what takes place in the television series Quantum Leap, although there is definitely much less Dean Stockwell.

Not so many Christmases ago Santa was for a trice right here in our little corner of the world, by a mystery of synchronicity that even he doesn’t understand having once again manifested exactly when and where he was needed most. On a Wednesday afternoon less than two weeks before Christmas, this good Noel spirit found himself hosted by the body of portly Mr. Porter in the small multipurpose room at Elsewhere Elementary School just as 10-year-old Elora was hoisted aboard the old man’s lap to go through the motions of telling him what she wanted for Christmas (she had long since ceased to believe in Santa Claus, at five years of age having interrogated the supposèd truth from her parents) and have her picture taken, as was the school’s tradition.

Through powers that came quite naturally to Santa, he knew immediately that Elora was an unhappy child. It had not always been thus. As good fortune goes, Elora was fortunate. She had never missed a day of school due to illness. She had many friends throughout her upper-middle-class suburban housing tract. She had a mother and father who loved her dearly and were able to provide her with far more than the basic necessities. For every Christmas that she could remember she had received everything she had wanted (she was not quite spoiled, but certainly indulged). All in all, she had been the happiest of little girls—until last Christmas, when her joie de vivre had been eclipsed by a shadow her parents could not explain.

It had started out just like any other Christmastime. As was the family custom, on the day after Thanksgiving Elora and her father went to a nearby Christmas-tree farm and carefully selected just the right Douglas fir (flocked, since the only snow seen around these parts filters to us by way of TV screens). Over the next few days the tree and house were decorated with a tasteful festiveness, and Elora set to work on her Christmas Wish List.

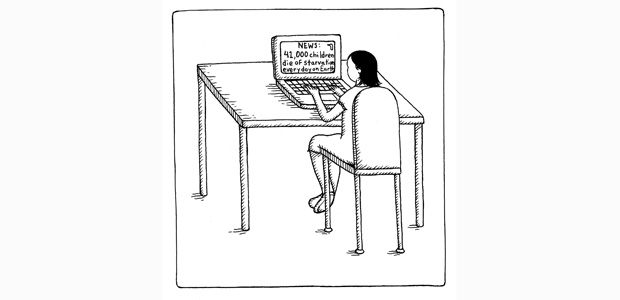

But that year she was nine, a year older and wiser and far more aware of the goings-on on planet Earth, mostly through the World Wide Web (between history and the news, even our most responsible and diligent parents with the best safe-browsing technology cannot protect us from the darkness in life). She knew that things were often quite unlike what she experienced in her loving home and quiet community. She knew that many children were so sick they had to live in hospitals and might never get well. She knew that many kids didn’t have moms and dads or anyone to love them. She understood that poverty meant some people were lucky to get anything at all for Christmas, even just something good to eat. She knew about natural disasters and war. She had even seen a story about kids at a little school like hers getting shot as they sat in their classroom, kids with names like Jaden and Kaia and Lizzie and Maren, kids just like Elora and her friends.

She couldn’t stop thinking about this as she sat cross-legged on her bedroom floor, tapping her navy blue notebook with a brand-new No. 2 pencil. A week later when her mother asked about the Wish List, Elora began to cry and said she didn’t want anything, and how could they celebrate Christmas in a world so awful?

It was the unhappiest Christmas the family had known. Elora’s mom and dad gave Elora many very thoughtful presents, but Elora barely said “thank you” and asked to be excused to go to her room as soon as she had unwrapped them. The next morning she barely looked in her stocking, and she ate only three pieces of chocolate and one pink Peep. Her parents were very worried. After winter break ended they had Elora talk to Ms. Sanchez, the school counselor, but Ms. Sanchez couldn’t change Elora’s mind about the awfulness of the world. After all, everything Elora thought was awful was happening all the time—perhaps not here, but somewhere. Besides, Elora’s new worldview wasn’t interfering with her schoolwork or socialization, so maybe it wasn’t something to worry about. Kids go through phases, Ms. Sanchez told Elora’s parents.

It was the unhappiest Christmas the family had known. Elora’s mom and dad gave Elora many very thoughtful presents, but Elora barely said “thank you” and asked to be excused to go to her room as soon as she had unwrapped them. The next morning she barely looked in her stocking, and she ate only three pieces of chocolate and one pink Peep. Her parents were very worried. After winter break ended they had Elora talk to Ms. Sanchez, the school counselor, but Ms. Sanchez couldn’t change Elora’s mind about the awfulness of the world. After all, everything Elora thought was awful was happening all the time—perhaps not here, but somewhere. Besides, Elora’s new worldview wasn’t interfering with her schoolwork or socialization, so maybe it wasn’t something to worry about. Kids go through phases, Ms. Sanchez told Elora’s parents.

But as Christmastime came ’round again, Elora was increasingly irritable and disaffected, disgusted by all the shopping and commercials for presents that you should buy your loved ones to show them that you care. “I don’t want us to celebrate Christmas anymore,” Elora announced to her parents three days before Thanksgiving. “It’s a stupid, selfish holiday!”

Her parents were concerned and confused, but they attempted to remain festive. Just like every year, on Friday her father went to buy a flocked Douglas fir…but Elora refused to come with him to pick out the tree. Her parents decorated the house…but Elora wouldn’t help. Clearly, asking for her Wish List was a nonstarter.

Santa knew all this as Elora situated herself without looking him in the eye. But to keep up appearances he said exactly what old Mr. Porter would have said: “Ho-ho-ho! What’s your name, little girl?”

“Elora,” said Elora, civil but sad.

“What a pretty name! And what do you want for Christmas, Elora?”

“I don’t want anything. Christmas is a stupid holiday.”

“Oh no-ho-ho,” Santa rejoined. “How can you say such a thing?”

“Wanting toys or anything for Christmas is selfish when some people don’t have parents or houses or food or legs and so many terrible things happen all the time. I wish Christmas would go away forever.”

Santa was at a loss. He had dealt with precocious children before, but this was something new. Was it fallout from living in so-called modern times? (He was still puzzled by the Internet, for example, with which one could circumnavigate the world more quickly than even his incorporeal self.) Whatever the cause, he had no ready answer. In many ways the world was awful, of course. In any case, this was neither the time nor place to conduct a debate on the relative merits of Christmas or the world at large, so he let the matter drop and eased Elora to the multipurpose-room floor. By the time the next student in line (a second-grader with a long list of Christmas desires he was more than happy to share) was on Mr. Porter’s lap, Santa had transmigrated to a town in North Ontario to see a young girl named Neely with a Christmas crisis of her own. (But that is another story.)

***

Elora was even sadder this Christmas Eve than she had been the year before, and after dinner she asked to be excused to her room. Her parents tried to convince her to open her presents, but their blandishments only upset her, and they were left alone to exchange the gifts they had purchased for one other. They appreciated each other’s thoughtfulness, but they could not help but be distracted by sadness and worry over their daughter’s Yuletide turn. Deciding that the best thing this year was not to fill up her stocking, they went to bed after taking turns (as they always did) surreptitiously inserting a few goodies into each other’s stocking.

Elora had fallen asleep especially early, so she was the first to rise in her household that Christmas Day. She lay in bed for a full hour and would have stayed there all day to let Christmas pass without her, had she not become hungrier by the minute, until finally the need for nourishment drove her downstairs. Quietly she moved towards the kitchen for a bowl of cereal, when a strange vision at the fireplace stopped her in her tracks. Sticking out of her stocking there appeared to be a rectangular box adorned with a sort of wrapping paper the likes of which she had never seen. This was not a sheet of unchanging color, but a vibrant, prismatic sheen, a gallimaufry of light chaotically rippling across the package more rapidly than her visual system could properly process, in patterns far more complex and brilliant than she had seen in videos of certain octopi and those cute little cuttlefish. No billboard or fiber-optic flourish could compare to the spectacle in her stocking, and for a moment she was frightened. But she approached in wonderment, the pupils of her eyes dilating, the package titillating her optic nerve and occipital lobe. She stood at the hearth for an enraptured minute or two (her conception of time had gone a bit wonky), before tentatively tapping its top with a fingertip. It seemed solid and safe. She rested her palm on the kaleidoscopically breathing surface, then gently gripped it with both hands and removed it from her stocking. It was far less weighty than she expected, feeling like it might take flight.

Although she had never laid eyes on such technology (if that’s what it was), clearly this was a sort of wrapping paper and was waiting to be torn, so she clawed delicately at the colors, which tore just like paper always does (at least if all paper felt so watery). But instead of a revealing a box or any sort of structural support, the paper had held its own shape. There seemed to be nothing there.

But don’t you find in life that many things are not at all what they seem? Rather than nothing, the unwrapping of Elora’s sole stocking-stuffer suggested something like a thought—although “thought” is definitely not quite right. Sometimes we think in images. Something we think with words. Sometimes we are subject to sensations of a peculiarly mental sort; such is the mystery of the mind. Elora was given to understand a sentiment, an alignment toward existence, imparted to her from Santa (with whom she now knew she had encountered nary a fortnight ago). And were we confronted with the necessity of rendering Elora’s engulfment as words, we would shake our heads in frustration and sigh, and then perhaps scribble something along these lines:

To receive is good

when it pleases

the giver.

Having must be first;

then comes giving.

And when you

are happy and can

truly give, what

will you want?

Elora’s parents had come downstairs, and they found their daughter at her stocking, crying. “Oh, baby,” her mother said, rushing to her side, “what is it?” She considered the filled stockings on either side of Elora’s empty one and exchanged a knowing, guilty glance with her husband.

“We’re sorry,” the father said, kneeling down, an arm around his daughter’s shuddering shoulders. “We just thought….”

But then they could see that although Elora was overflowing with tears, she was happy, joyous even, and she hugged both of her parents to her with all of the loving might in her little body.

“Elora honey,” her mother laughed, “what is it? My goodness, what’s this all about?”

Elora tried to speak, but the happy tears would not stop. She looked to where she had dropped Santa’s special Christmas wrapping (what else to call it?), but it was nowhere to be seen. Elora began to laugh. Then, finally, she found her voice.

“Thank you!” she said. “Thank you so much for all my wonderful gifts!”

“But you don’t even know what they are,” her father said.

“It doesn’t matter,” Elora said. “Or, I mean, it does. But not really. Oh, I don’t know!” she laughed, and hugged her parents again. “Thank you for everything you’ve given me. And to each other. Oh, gosh! I’d forgotten how hungry I am! Can we have Christmas pancakes?”

“It doesn’t matter,” Elora said. “Or, I mean, it does. But not really. Oh, I don’t know!” she laughed, and hugged her parents again. “Thank you for everything you’ve given me. And to each other. Oh, gosh! I’d forgotten how hungry I am! Can we have Christmas pancakes?”

Her parents had no idea what to make of Elora’s change of mood, and they wondered whether she ought to spend more time with Ms. Sanchez so that the counselor could determine whether Elora was bipolar and should be put on lithium. But this notion passed, and the three enjoyed a wonderful Christmas Day. And when it was Elora’s bedtime, after her mother and father had tucked her in and kissed her goodnight and wished her a merry Christmas one final time, Elora snuck out of bed and opened her navy blue notebook, and with her brand-new No. 2 pencil she began to compile a Christmas Wish List for next year, a list of all of the things she would like to give her parents in 364 days. She could hardly wait.

—Original artwork by Dave Van Patten