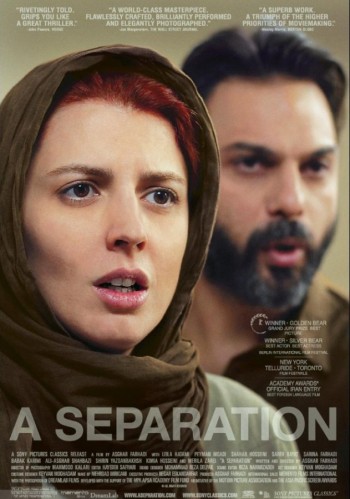

10:00am | It’s Oscar month at the Art Theatre, apparently, as Best Picture winner The Artist has just given way to Best Foreign Language Film.

That language is Persian, and that film is A Separation, which starts out seeming as simple as the title (or at least the truncated translation of it we’re getting Stateside): Simin (Leila Hatami) is petitioning the court for a divorce from Nader (Peyman Moadi) — not because he’s given her the customary grounds for divorce or even because she doesn’t love him, but because he refuses to leave Iran with her and their 11-year-old daughter, Termeh (Sarina Fahadi), and begin life in a less oppressive society. But it’s a move Nader is unwilling to make because it has fallen to him to care for his Alzheimer’s-ravaged father (Ali-Asghar Shahbazi, in a thankless, heartbreaking role).

With Simin gone (though still nearby, at her mother’s), Nader hires Razieh (Sareh Bayat) — obtained by way of one of Simin’s acquaintances — to care for his father while he is at work. But it’s a job the four-months-pregnant and fundamentally religious Razieh is ill equipped to deal with, which leads to…

If I kept going on in that vein I’d reveal the entire plot. But if writer/director Asghar Farhadi’s main focus were the ways each of our decisions can ramify, I might be encouraging you to stay home and rent Run Lola Run. But the real story Farhadi is telling is of the idiosyncratic moral and ethical tensions — sometimes including a tug of war between the two — that reside within each of us.

There’s no question that Nader is as Simin describes him to the judge in the opening scene (“a good, decent man”), and we certainly feel for him at every turn. But Farhadi has crafted his characters with at least some degree of moral ambiguity, populating A Separation with souls in torment when faced with extremity, doing what they see as being the best they can do by the lights with which the contingency of their idiosyncratic experience has equipped them.

The unexpected focus of the various struggles (internal and external) that roil around her as cause-and-effect plays out unpredictably is Termeh, who is just old enough to understand these struggles, including the ones bubbling up in her developing conscience. (A late shot of her locking eyes with Razieh’s 4-year-old daughter is a masterstroke.)

Early scenes with her father give us some insight into the forces that are shaping her to be an independent thinker. At a gas station, for example, her father shows no sexist deference to her gender as he walks her through pumping gas, right down to having her go back to the cashier when he tries to take advantage of her youth and/or femininity. Later while helping her with homework he points out that a teacher’s error is not to be glossed over just because it emanated from so-called authority. “What’s wrong is wrong,” he exclaims, “no matter who says it.”

Everything about this film is understated, from the acting (never overly emotive, even when playing rage) to the subtle directorial choices and simple cinematography to the complete absence of a score. A Separation is the antithesis of manipulative filmmaking. If the audience feels something, it’s completely earned.

Perhaps the most “cinematic” element of the film is Hayedeh Safiyari’s editing, which with a skilled unobtrusiveness jumps us forward in the action in places where seeing more detail with give us needless looks at mere connective tissue. A Separation is nothing if not economical.

If you can sit still and process the verisimilitude on screen, there is much to be felt. But what you won’t get is having your preconceptions satisfied. Despite the opening scene’s reference to Iranian society as oppressive, A Separation has no political axe to grind. Iran is simply the setting for this story, a background but not a major character. Rather, this is a story about people muddling through with their morals and ethics and self-interests, moveable forces that sometimes come into direct conflict with each other. Because those aspects of life can never really be separated from one another, can they?

Art Theatre of Long Beach, 2025 E. 4th Street. (562) 438-5435, www.arttheatrelongbeach.com