Filmmaker Matthew Mishory will be on hand at the Art Theatre on Wednesday, December 12 for the opening night premiere of his first full length feature, A Portrait of James Dean: Joshua Tree, 1951. Also on hand will be co-star and producer Edward Singletary Jr, producer Robert Zimmer Jr., and other members of the cast and crew. The week-long run, presented by the Long Beach Cinematheque, ends on Tuesday, December 19 with another appearance by Mishory.

Mishory says that the film found him.

“My father came to the United States as an immigrant at 16 to study the violin at Juilliard, and learned to speak English by going to the cinemas. He was lucky enough to see the James Dean films in first run and, when I was a very small boy, the first feature film I remember him showing to me was East of Eden. Needless to say, it made an impression. So I have been living with these images of James Dean my entire life. Even as a child, I was aware of a very special and very unusual quality to his acting.

“Dean changed the way actors perform on screen. And he developed his own unique and interesting theories about acting, and the necessity of living life (and art) in extremes. He was, in that way, a modern Arthur Rimbaud. Which is why our film actually starts with Rimbaud–to find a context for this very iconoclastic and interesting life Dean led.

“The desire to make the film comes from a personal place. It always starts that way for me. It comes from growing up with those memories of the Dean films. And then, as we got into the research, I was very moved by how difficult it was for him to get anywhere in Los Angeles. He was just a kid from Indiana who came to Hollywood with a dream, and a new way of seeing things–and he got eaten alive.

“Ultimately, he made the sort of impact he always hoped to — but not before a significant period of struggle. Dean was a very complex and sometimes difficult person. But there was also a very admirable artistic nobility about him. He never compromised.

“For Dean, like so many actors, initially it was just getting cast in anything — getting someone to take notice. His period of great success was so very short. In our film, we focused on a very different period — the period before all of that. Many people do not realize that four years lay between Dean’s dropping out of UCLA and making his first feature for Elia Kazan. Our film is very narrowly set in that interesting — and formative — period. It addresses the question I always find the most fascinating: What are the antecedents to a remarkable and unconventional life?”

Mishory drew on a variety of sources in crafting the narrative, including biographies, autobiographies of contemporaries, and personal testimony of people surviving the era.

“The latter was perhaps the most fascinating. For instance, Edward Singletary, Jr., who plays Roger, spent some time with a surviving friend of Rogers Brackett (the basis of the character). So his performance contains these wonderful little moments of authenticity that can only come from interaction with a contemporary of the character.”

Still, it was not Mishory’s intent to create a biopic, or even a biographical film in the traditional sense.

“It is a portrait, and we use all of the tools in the portraitist’s kit. We started with the histories (messy and sometimes contradictory as they might be), and many scenes in the film are ‘factual’ — that is based on recollected or recorded histories. But some portions of the film in the desert are fictionalized to create a sort of emotional and symbolic element to the story. And some other moments of the film are stylized to make a point.

“The goal is always ‘truth.’ ‘Fact’ is a loaded word — and not a very interesting argument to have. ‘Truth’ is why we make films.”

Mishory feels he uncovered some truths about Dean.

“He was truly an outsider everywhere he went. Even in the brief period of ‘success,’ he was never quite at ease. And he was equally driven by his exceptional but also his enormous ambition, but there was a price to pay for that ambition. The singularly driven and committed man makes personal compromises — and is a difficult man to love. We do explore that in the film.”

Mishory says that most fans know very little of the man behind the iconic representations on souvenir t-shirts and posters.

“Dean was the first movie star to portray young people on film in a compelling and realistic way. He was probably also the first truly self- aware, post-modern movie star. I think that, while Dean was very cynical about the restraints of the Hollywood system, he was also aware of its many possibilities. Dean was not really the man generations of fans have seen posing in those photographs, but he knew exactly what he was doing.”

One of the striking elements of Mishory’s film is the sense that the actors seem more at home in the 50’s than in the modern era, that they somehow fell out of a time capsule.

One of the striking elements of Mishory’s film is the sense that the actors seem more at home in the 50’s than in the modern era, that they somehow fell out of a time capsule.

“Parts were written for Dan Glenn, Dalilah Rain, and Edward Singletary. Dalilah had been in my previous film, also a period piece, and I felt she embodied that glamorous 50s look — with a necessary edge. Edward was always the only actor who could ever play Roger–who could find a sympathetic and interesting way into his soul. I love his performance. And Dan Glenn, who audiences often point out looks a lot like Rock Hudson or John Gavin, plays The Roommate. His character is, in many ways, the soul of the film. Dean was somebody who blew through people’s lives, leaving an indelible impression. He was impossible to hold on to.

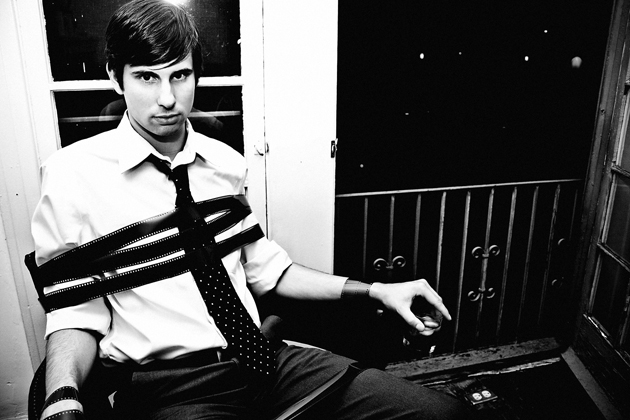

“As for James Preston, the wonderful young actor who so bravely and intelligently plays James Dean — he came to us through the casting process. A break-down went out, and thousands of actors were submitted. James was referred through Dalilah, and came in for the call-backs. As soon as he stepped in to the room and did his thing, we knew we had our guy. James Preston was a kid from Texas who dropped out of art school, got in his truck, drove to LA, and worked hard at being an actor. There was a nice parallel between his story and the Dean story. I think it must have been daunting for James [to portray Dean], but he’s a fearless actor — all the good ones are. We both took a risk.”

Mishory eschewed playing into the inflated ‘icon’ status that Dean’s legacy has suffered from.

“That was why I was far more interested in the period in Dean’s life in which nobody had even heard of him. The decades of ‘icon status’ that have followed are really just a marketing conceit and, as some critics have pointed out, our film is not really just about Dean. It’s also about Hollywood — and a system that persists to this day.”

The film has been on the international film festival circuit for months.

“It has taken us all over the world and now to theatres, so of course we’re thrilled. The reception has not been without controversy, and the film is stylistically very different from a traditional Hollywood movie and thus not for everyone, but overall the response has been fantastic. The best part of the festival tour has been the conversations we have had with audiences–each with a different perspective.”

This controvery stems from what Mishory describes as the film’s “omni- sexuality,” and the depiction of Dean as “non-heterosexual.”

“The LA Weekly pointed out that Elizabeth Taylor said the same thing on primetime television. What is common knowledge can hardly be controversial. Others might disagree, but that’s a conversation we’re happy to have; that’s why we make films. I’ve always said that, if you’re open to a slightly different experience in terms of form and content, this film will take you on a journey.

“I made the film the way I did to start a conversation–not just about Dean or history–but also about how we can make movies. Working on a modest budget, without a big studio looking over my shoulder, I could work in a slightly different way. I’m really proud of what my cast and our team came up with.”

Mishory is also proud that the movie was shot on film, and not digitally.

“It would not have made sense to shoot this project, set in 1950 and 1951 (a time in history that most people know through the movies — through classic movies), on anything other than film. But I have also never really warmed up to video, and will always prefer film. I find it not only more beautiful and more special, but also more emotional. There is a living, breathing sadness and warmth in the tangibility of the celluloid object.

“Apichatpong Weerasethakul was correct when he said that the photochemical process best replicates the mechanism by which the human eye reacts to light. I also love the variety and textures of film—stocks, gauges, and varying grain structures. I have always used small gauges in my work, and while much of A Portrait of James Dean was shot on 35mm, there are blasts of super16 and super8 here and there.”

Mishory credits the curatorial genius of Long Beach Cinematheque’s founder and Executive Director, Logan Crow, for bringing the film to Long Beach, and the Art Theatre.

“Logan is a terrific advocate for arthouse and independent cinema. When he approached us about doing this run, (Long Beach Cinématheque’s first theatrical run), it was definitely something we wanted to be a part of. And who can possibly argue with opening a film in a still-operating 1920s Art Deco picture palace. The run will expand to other cities in the New Year, but we’re truly excited to kick it off at the Art.”

—

Tickets are available from the Art Theatre’s box office, or by visiting LBCinema.org.

To learn more about Matthew, visit MatthewMishory.com.

To learn more about the film, visit JoshuaTree1951.com.